With Bob Iger returning to Disney, let’s revisit his Ride of a Lifetime

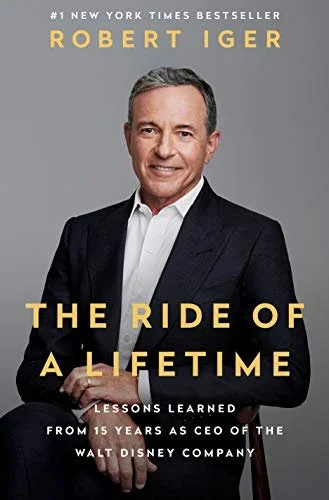

The return of Bob Iger to the CEO role at Disney – most likely for only a short time -- makes it easier for leaders, employees, vendors, and customers to get a sense of what might be coming next. I suspect a lot of people have picked up (or dusted off) a copy of Iger’s 2019 memoir, The Ride of a Lifetime, to learn a bit more of what he says he learned during his previous 15-year tenure as CEO.

I put it that way because you can never be totally sure with books like this whether they’re an authentic representation of the author’s philosophy or a sanitized, ghostwritten version.

Iger has been criticized for his failure to find the right successor for the complexity of the Disney business model. Some think his main job is to rectify that failure, even if it means selling the company to someone like Apple.

He arrived at an employee town hall at the end of November shortly after distribution of internal memos warning of impending layoffs. The Hollywood Reporter said he acknowledged austerity measures and gave the presence of a steady hand to what the publication said was “palpable” employee excitement.

Iger outlines 10 principles that strike him as necessary to true leadership. You’ll have to read the book for more detail, but it strikes me as a pretty good list: Optimism, Courage, Focus, Decisiveness, Curiosity, Fairness, Thoughtfulness, Authenticity, The Relentless Pursuit of Perfection, and Integrity.

As I reread the book this past week, juggling it with a brand pivot and 2023 planning, I liked Iger’s observation about communicating the “three-legged stool” of any presentation or plan: “Priorities are the few things that you’re going to spend a lot of time and a lot of capital on. Not only do you undermine their significance by having too many, but nobody is going to remember them all. “You’re going to seem unfocused,” he said. “You only get three. I can’t tell you what those three should be. We don’t have to figure that out today. You never have to tell me what they are if you don’t want to. But you only get three.”

He goes on to advocate for communicating those priorities clearly and repeatedly – good advice for everyone if they’ve done the work of thinking them through.

For Those of You Who Prefer Disney+ to Reading About Disney…

Here are 15 takeaways from the book (many of them from the Lessons to Live By appendix) that might be valuable whether you’re working for him, reporting to him, buying from or selling to him, or just running a completely non-related business. I loved this book (I read from Kindle and had to delete some of my highlights just to get them to download.

You can buy it here on Amazon – and yes, I’ll make a few cents – or you can head over to your favorite independent bookstore, which my daughter prefers me to say.

1. I talk a lot about “the relentless pursuit of perfection.” In practice, this can mean a lot of things, and it’s hard to define. It’s a mindset, more than a specific set of rules. It’s not about perfectionism at all costs. It’s about creating an environment in which people refuse to accept mediocrity. It’s about pushing back against the urge to say that “good enough” is good enough.

2. Take responsibility when you screw up. In work, in life, you’ll be more respected and trusted by the people around you if you own up to your mistakes. It’s impossible to avoid them; but it is possible to acknowledge them, learn from them, and set an example that it’s okay to get things wrong sometimes.

3. True integrity—a sense of knowing who you are and being guided by your own clear sense of right and wrong—is a kind of secret leadership weapon. If you trust your own instincts and treat people with respect, the company will come to represent the values you live by.

4. Ask the questions you need to ask, admit without apology what you don’t understand, and do the work to learn what you need to learn as quickly as you can.

5. Managing creativity is an art, not a science. When giving notes, be mindful of how much of themselves the person you’re speaking to has poured into the project and how much is at stake for them.

6. I tend to approach bad news as a problem that can be worked through and solved, something I have control over rather than something happening to me.

7. Of all the lessons I learned in my first year running prime time at ABC, the acceptance that creativity isn’t a science was the most profound. I became comfortable with failure—not with lack of effort, but with the fact that if you want innovation, you need to grant permission to fail.

When the Boss Tells You to Avoid Selling Trombone Oil

8. My former boss Dan Burke once handed me a note that said: “Avoid getting into the business of manufacturing trombone oil. You may become the greatest trombone-oil manufacturer in the world, but in the end, the world only consumes a few quarts of trombone oil a year!” He was telling me not to invest in small projects that would sap my and the company’s resources and not give much back. I still have that note in my desk, and I use it when talking to our executives about what to pursue and where to put their energy.

9. As a leader, if you don’t do the work, the people around you are going to know, and you’ll lose their respect fast. You have to be attentive. You often have to sit through meetings that, if given the choice, you might choose not to sit through. You have to listen to other people’s problems and help find solutions. It’s all part of the job.

10. People sometimes shy away from big swings because they build a case against trying something before they even step up to the plate. Long shots aren’t usually as long as they seem. With enough thoughtfulness and commitment, the boldest ideas can be executed.

11. You can do a lot for the morale of the people around you (and therefore the people around them) just by taking the guesswork out of their day-to-day life. A lot of work is complex and requires intense amounts of focus and energy, but this kind of messaging is fairly simple: This is where we want to be. This is how we’re going to get there.

12. You have to do the homework. You have to be prepared. You certainly can’t make a major acquisition, for example, without building the necessary models to help you determine whether a deal is the right one. But you also have to recognize that there is never 100 percent certainty. No matter how much data you’ve been given, it’s still, ultimately, a risk, and the decision to take that risk or not comes down to one person’s instinct.

On Asking Yourself the ‘What Problem Am I Solving’ Question

13. Those instances in which you find yourself hoping that something will work without being able to convincingly explain to yourself how it will work—that’s when a little bell should go off, and you should walk yourself through some clarifying questions. What’s the problem I need to solve? Does this solution make sense? If I’m feeling some doubt, why? Am I doing this for sound reasons or am I motivated by something personal?

14. It doesn’t make any sense for us to buy you for what you are and then turn you into something else.

15. Looking back on the acquisitions of Pixar, Marvel, and Lucasfilm, the thread that runs through all of them (other than that, taken together, they transformed Disney) is that each deal depended on building trust with a single controlling entity…Steve had to believe my promise that we would respect the essence of Pixar. Ike needed to know that the Marvel team would be valued and given the chance to thrive in their new company. And George had to trust that his legacy, his “baby,” would be in good hands at Disney.

“Ask the questions you need to ask, admit without apology what you don’t understand, and do the work to learn what you need to learn as quickly as you can.”

Add this to the list of outstanding leadership books on the market. Buy it here on Amazon (affiliate link) or head over to your favorite independent bookstore, which is what Abby will do if she reads this since she refuses to read anything on a Kindle.

What’s your favorite takeaway from this list?